There is quite a bit of confusion regarding what tax equity is for renewable energy and how it can be taken advantage of. This is largely because tax equity structures are ubiquitously understood to be complicated, meaning many firms just don’t bother with them. That’s a mistake. Tax equity can be a powerful incentive for developing RE in the USA.

Companies that have managed navigate the system have been able to reap the benefits of tax equity structures, but new entrants can be deterred, therefore bypassing potential benefits.

What is Tax Equity?

Tax equity is where renewable energy and tax policy intersect. Basically, tax equity is a creative and complex way to split the benefits of installing and producing RE electricity from their corresponding tax benefits.

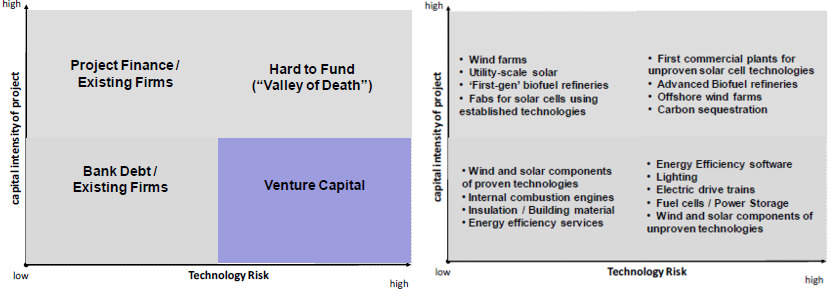

Tax credits, however, can only be used by clean energy developers who are profitable enough to pay larger amounts of taxes. Because of this, many smaller players, who are not very profitable cannot reap the benefits of tax credits. Hence, they must find an investment partner with enough income to be able to reap credible benefits from tax credits.

Installing renewable energy is subsidized by a tax credit. This means that a solar project developer/company/host wants to have the benefits of solar electricity production (via decreased utility bills) but does not the tax liability to use the tax credits, so it passes those credits to an investor who in return puts up capital to pay for the solar project. The objective is to reduce its own tax bill by receiving the tax deduction. Tax equity financing is primarily provided by large banks, insurers or big corporations which provide upfront investment in exchange for tax credits associated with the development of (usually) solar energy projects.

Example:

Take solar developer start-up, Sunny Ltd., who wants to develop a large solar PV project. The cost of the project would be $1m. Although such an investment in RE carries corresponding tax credits, Sunny Ltd. is currently not profitable enough to take advantage of them, so they decide to rope in a Tax Equity Investor. The Tax Equity Investor, represented by Capital One Bank, wants to apply the tax credits to their own corporate tax bill.

So Capital One Bank can put up, say 40% of the solar project financing, used as equity (the remaining 60% hypothetically will come from debt).

So if the bank puts up $400K in equity, they could hypothetically reduce their tax bill by a certain amount over the course of a contract.

State of the Market

According to specialized law firm Chadbourne & Park, the market is steadily increasing. The U.S wind and solar markets in 2015 saw $11.5 billion in new tax equity deals, up from $10.1b from the year before. According to John Eber, head of energy investments at J.P Morgan, of that 11.5b, $6.4b was secured in the wind marketplace for projects totaling 5,700 megawatts capacity. There was three main sponsors int he winds tax equity investors that completed deals totaling $1b each (47% of tax equity raised in 2015).

In the solar residential tax equity market, about $2.6b was raised by three leading residential solar companies, accounting for 90% of the residential market, (up from $1.9b in 2014). Eber went on to say that distributed generation and utility-scale solar marketplace accounted for an additional $2.5b in tax equity deals. Eber says there are about 20 active tax equity investors in the wind marketplace and 27 in solar, with some crossover, and of the 20 active investors in wind, 17 entered into deals in 2015.

The small number of players is attributed, in part to the complex nature of tax equity and the associated costs and in part due to the fact that tax equity investors must have very large tax liabilities, to justify such operations.

But be that as it may, it is still a huge increase if you consider that after the financial crisis, the number of Tax Equity Investors collapsed from 14 providers to just 5 (Jacoby, University of Pennsylvania Law Review), since in order to take advantage of tax equity, you need to have huge tax liabilities and the after 2008 fewer companies had the necessary tax liabilities to make tax credits attractive.

Before we have a look at a few tax equity structures used, bear in mind who the stakeholders are:

Tax Equity Agreements usually have three stakeholders, although sometimes the developer and host are the same:

- A Developer (ex. a solar PV installer like SolarCity or FirstSolar ) who identifies a potential solar project and decides to undertake the costs and risks of engineering, procurement, installation, and commissioning;

- The Solar Host who is usually either a residential or commercial building owner, and is interested in the benefits of solar power;

- A Tax Equity Investor who usually is an institution like a bank or a corporation like Google, that has to have two things:

- high tax liabilities, or at least high enough to make a tax credit attractive

- the liquidity necessary to undertake the development of a solar project.

The Tax Equity Investor has to agree to finance and own the project for a number of years and in return for undertaking the construction and ownership costs of the solar project the company will receive the corresponding tax deductions.

The Tax Equity Investor is the defacto owner of the physical solar panels, while the benefits go to the host, and once the Tax Equity Investor reaps in the desired returns brought by the tax credits associated with the solar projects they return ownership to the developer.

Tax credit structures can vary quite a bit, but here are the two most common types:

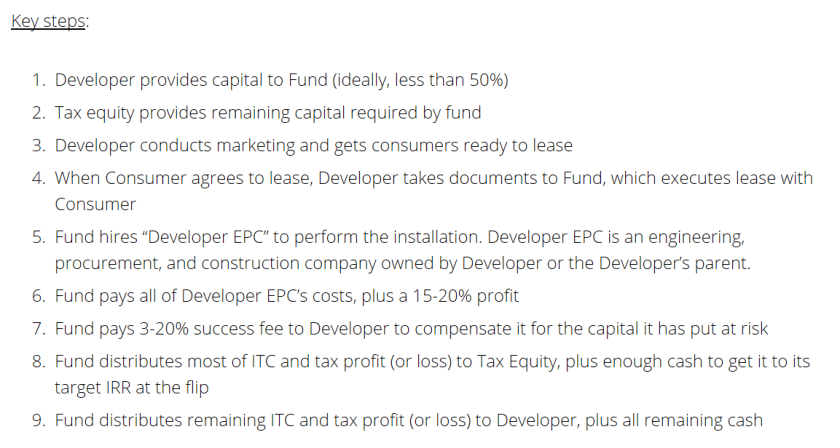

The Partnership Flip

As you can probably imagine, a Tax Equity Investor does not necessarily want to hang on to the solar panels for the entire life of the project- why would they? Enter The Partnership Flip. This is where the ownership of a project is owned by both developer and tax equity investor but in varying degrees.

The Tax Equity Investor and the developed enter into a partnership in which the have joint ownership of the solar project. Say, at the beginning of the project the ownership the Tax Equity Investor will hold 90% while and the developer will own 10%. Progressively, as the Tax Equity Investor begins to reap the rewards of the tax credits, the ownership of the project will begin to “flip”, whereby the Tax Equity Investor will own 60% and the Developer 40%…then 50%-50% until it is 10%-90% for the Developer.

Sale – Leaseback Agreement

This agreement sees the solar developer selling the project to the tax equity investor and then the tax equity investor leases it back to the solar developer. It’s actually simpler than a partnership, because all the tax benefits pass directly to the tax equity invest right away, whereas with a partnership, years pass before the Tax Equity Investor reaps all the benefits.

The Developer will install, operate and maintain the project and a Host will agree to purchase the power generated from the project, via a PPA.

The Investor keeps all the tax benefits and receives payment (cash) in the form of rent from the solar developer. The developer’s revenue from the PPA is used to make rental payments under the lease. The developer has a taxable gain on the sale of the project to the extent that the value of the project exceed the cost to build it. Indeed, the developer will usually have the option, exercisable at the end of the lease period, to buy the project from the investor at its fair market value.

The developer and the tax equity investor are like to two passengers in a car, when the car hits a bump, they are both impacted.

With solar and wind installations predicted to increase, 2017 will definitely see more tax equity deals for renewable energy, but what remains to be seen is if investors will be able to keep and meet the capital requirements of the industry.

Cover Photo: Ian Waldie/ Getty Images