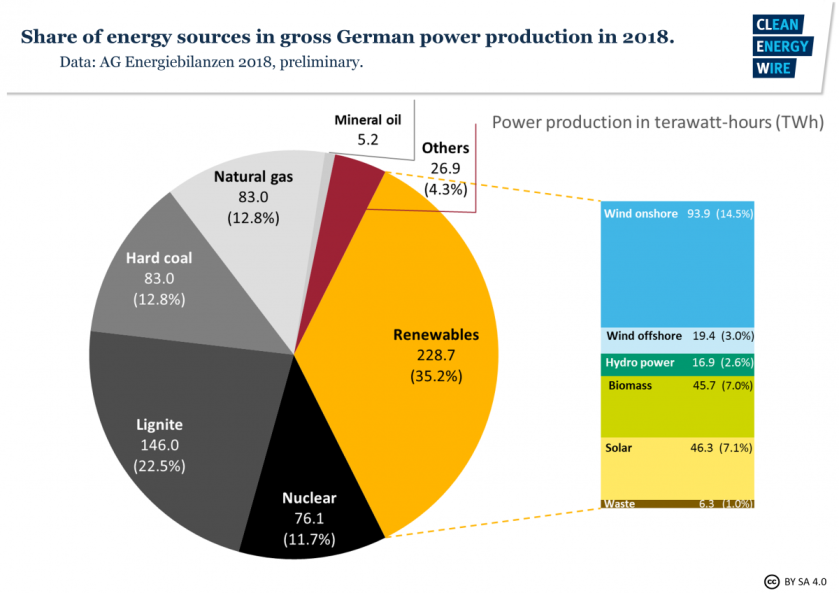

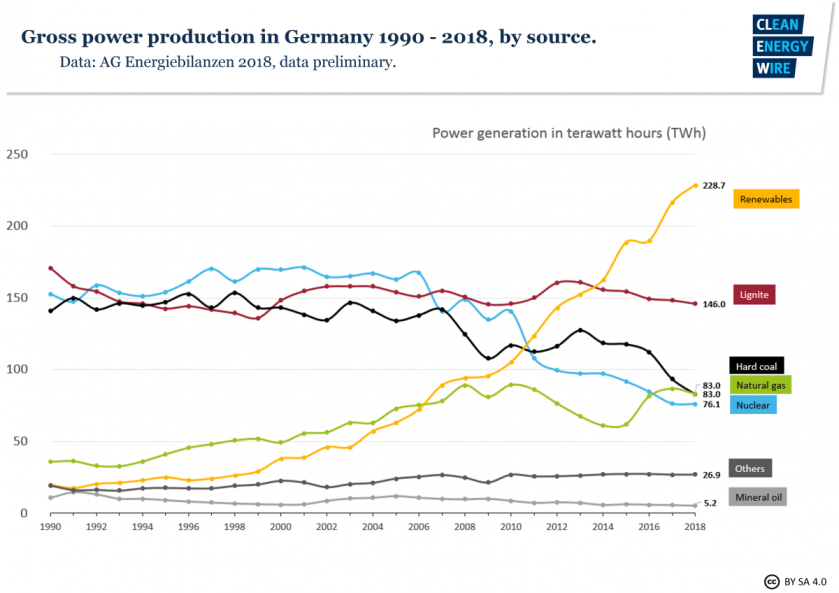

According to the Munich based Fraunhofer Institute, Germany’s renewables generated more electricity than coal in 2018 for the first time ever, with renewables providing 40% of the annual produced electricity and coal provided just 38%.

The growth in renewables can be attributed, in part, to:

- a prolonged hot sunny summer across Germany helping produce more renewable energy this year than last year, increasing solar output, by adding 3.2 gigawatts (GW) of solar to an existing 45.5 GW last year.

The remainder of Germany’s 2018 electricity production came from gas plants and nuclear plants.

While Germany did break ground, and on its own, this is great news, there are two sides to this story that make this achievement less impressive then it sounds.

✨All that glitters is not green✨

For starters, it stands to reason that if the solar energy grew, at least in part because of favourable weather rather then sustainable growth, then this growth is accidental rather then structural. So what could have been expected of those figures had the summer been rainy and cloudy?

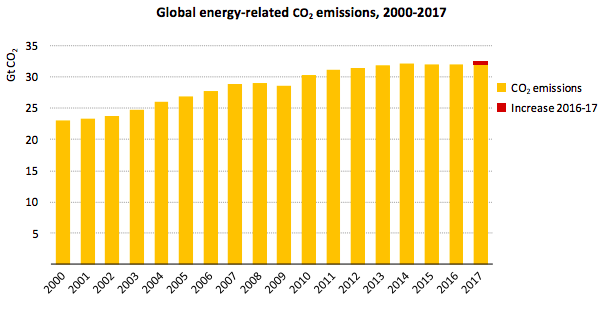

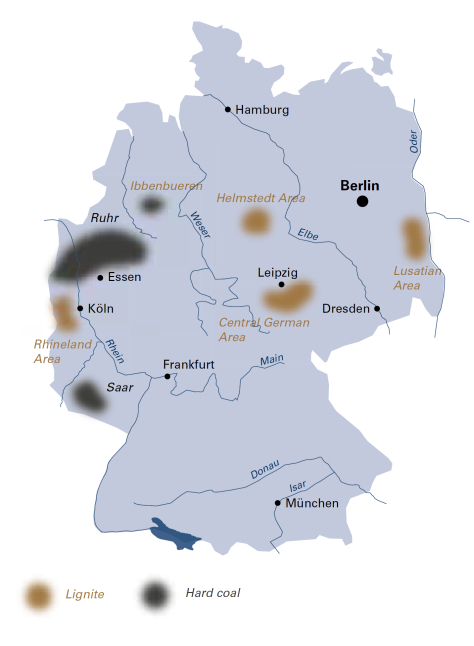

Secondly, coal and lignite* (dirtiest of all fossil fuels with relation to carbon dioxide emissions — but also the cheapest) still account for more than 1/3 of Germany’s electricity needs. Closing all of the country’s roughly 120 coal-fired power plants may take over 20 years, according to the government. Moreover, in 2011, following the Fukushima accident, the government decided to shut down 20% of the country’s nuclear reactors and close the rest by 2022. With nuclear on its way out, can we realistically 11.7% of Germany’s energy mix to replaced by renewables in a timely manner?

💸High Cost for Low Rewards?💸

Former Green environment minister Jürgen Trittin famously said that the burden placed on German households by the renewable energy surcharge would amount to “only around one euro per month, the price of a scoop of ice cream.” But the regular addition of renewables to the German power grid meant that the German taxpayer’s electricity bill was quickly inflated by the renewables surcharge, making Trittin’s well-intentioned comparison obsolete and quasi-comical.

Let me be clear: public dialogue about the energy transition’s price tag is propelled by a characteristic of Germany’s payment system green energies: consumers pay a renewables surcharge in their electricity bills. While this method may be more transparent than many alternatives based on direct state subsidies, it also elicits public debates about the costs. If the German electricity generation is what it is today, we have the German taxpayers to thank for it.

As of 2018, the surcharge made up 23% of the power price paid by an average household. In other words, German electricity bills would be 23% cheaper if renewables did not exist altogether. However, new research led by Alberto Gandolfi from Goldman Sachs, shows that from now onwards the marginal capacity that is going to be added to the system is going to be deflationary, meaning that the surcharge accounts for old and less efficient renewable energy, and the new highly efficient renewable which will be added from now onwards will have to potential to decrease the surcharge.

Bearing in mind that the cost of solar PV has plummeted by about 80%, wind (both offshore and onshore) has dropped by about between 50% and 70% since 2010, therefore Gandolfi’s research seems likely to materialize in the near future.

Nevertheless, in spite of the higher energy bills, public opinion has remained supportive of the energy transition. Research conducted in 2017 by the Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies in Potsdam found that 88% of those surveyed support the strategy to cut emissions.

Bear in mind that the energy transition’s costs are difficult to quantify. Estimates of the total amount of annual investment vary from 15 to 40 billion euros or 0.5% to 1.2% of Germany’s current GDP of around 3,200 billion euros.

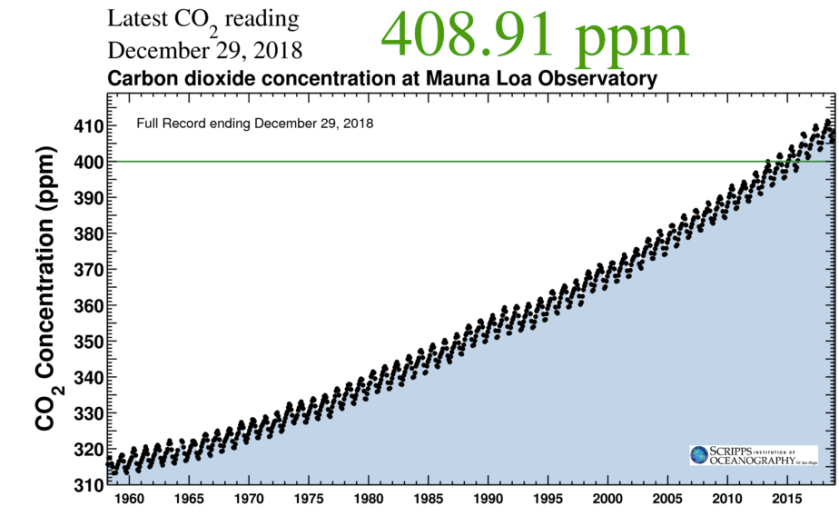

Missed Targets

The German Bundestag has committed to reducing Germany’s greenhouse gas emissions by 40% by 2020, by at least 55% in 2030, by at least 70% in 2040 and by 80-95% in 2050 compared to 1990 levels. Germany’s ambitious targets also sought to reduce German dependence on imported energy, to shift electricity from fossil fuels to green sources, to make transportation and buildings more energy efficient.

Germany’s progress in achieving its targets if falling widely short of expectations. The government recently admitted that they will fall short of their 2020 target by 8%, achieving only 32% reduction of emissions since 1990 vs. the 40% target and will thus fail to meet its goals as set out in the 2015 Paris Agreement.

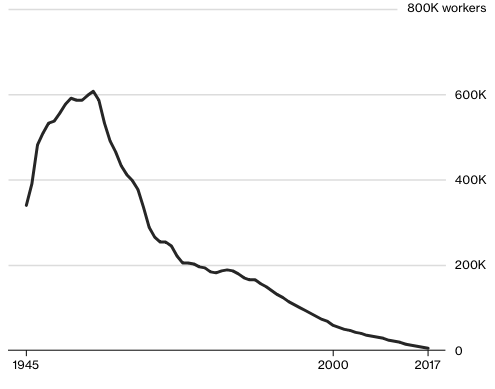

If we look above at the above electricity production for Germany, coal (meaning Hard coal and Lignite) plays an enormous role. While Hard coal consumption has dropped, lignite has not decreased significantly. The reason for this is that lignite coal is too cheap and reliable. The second reason is that touching lignite is a sensitive political issue, even in Germany, due to the roughly 22,500 people whose jobs depend on it. Although employment in the coal industry is on its way out (see above below), the jobs are located in economically fragile areas, where losses would be felt deeply.

German Coal Employment

However, the relative cheapness of lignite is explained by the fact the price of carbon is not factored into its price. This means that is we were to see the real price of coal, with the price of pollution factored into it, it would not be cheap at all. In any case, the market favours “cheap coal” and this is why its use has barely decreased, despite falling profits from coal plants.

Moreover, Germany’s target to put 1 million electric vehicles on the road is clearly going to be missed, since by the end of 2017 there were 131,000. The government’s strategy of aEUR 4000 subsidy per vehivle on green vehicles is all but wasted without a coherent and structured strategy to switch conventional vehicles with green vehicles.

The fact that Germany is set to miss its 2020 targets by 8% is terrible news. The OECD has called on Germany to take additional measures to make up for the loss, but nothing concrete has come out it., yet.

Therefore, although German renewables surpassing coal in electricity generation can be seen as a glimmer of hope in an otherwise grey backdrop, there are structural problems that stand in the way of achieving necessary reduction targets. And if Germany cannot achieve its own targets, then who can?

*Lignite, a.k.a brown coal, is a soft, brown, combustible, sedimentary rock formed from naturally compressed peat. It is considered the lowest rank of coal to its relatively low heat content and high moisture level, which means that it is very polluting and highly inefficient. It has a carbon content around 60–70%.

Required Reading: Energiewende 2030: The Big Picture http://bit.ly/2FfCdIT