Preamble: I would like to point out that I truly prefer not to engage in these types of discussions (read: I’m over it), because the sources of information that are available to me, are available to everyone else. I also do not consider it my duty to educate every Tom, Dick, and Henry on climate change. However, in light of recent developments, we will probably be encountering a more energized brand of deniers, so here is a non-exhaustive list of answers I took from Robert Henson’s Rough Guide to Climate Change.

Since the days of Roger Revelle, the pioneering oceanographer whose body of work was instrumental for our understanding of the role of greenhouse gas emissions in our atmosphere, deniers developed certain criticisms that are still popular today. I believe that these arguments will keep on cropping up for as long as there is a “debate” on climate change, so it’s best that we equip ourselves with appropriate answers.

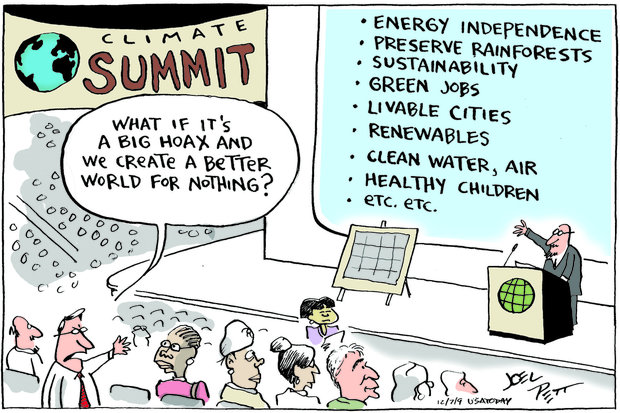

Taken to the extreme, anti climate change arguments can be summed up in the following quote:

“The atmosphere isn’t warming; and if it is, then it’s due to natural variation; and even if it’s not due to natural variation, then the amount of warming is insignificant; and if it becomes significant, then the benefits will outweigh the problems; and even if they don’t, technology will come to the rescue; and even if it doesn’t, we shouldn’t wreck the economy to fix the problem when many parts of the science are uncertain.”

“But the atmosphere isn’t warming….”

According to an ongoing temperature analysis conducted by scientists at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS), the average global temperature on Earth has increased by a mean of about 0.8° Celsius (1.4° Fahrenheit) since 1880. Two-thirds of the warming has occurred since 1975, at a rate of roughly 0.15-0.20°C per decade.

This arguement, has seeminly been put to rest, yet deniers seem to resist it, possibly because they do no think that a global mean warming of 0.8°C is a big deal. Here is a more vivd statistical example of what that means:

This is a bell curve mapping distribution of temperature anomalies over 60 years. To the left are temperatures colder than average and to the right are temperatures hotter than average. The mean is shifting and the distribution is broadening rightwards. The right tail of the distribution is reaching 4 and 5 sigma, which are probabilities that were unheard of decades ago. The anomalies occurring at 4 and 5 sigma are (were) rare massive heatwaves, storms, and floods, which are becoming more common then ever.

“Okay, but I still went skiing this winter…”

The weather and the climate are two different things. The difference between weather and climate is a measure of time. Weather is what conditions of the atmosphere are over a short period of time, and climate is how the atmosphere “behaves” over relatively long periods of time. We talk about climate change in terms of years, decades, and centuries. The weather is forecast 5 0r 10 days ahead, but the climate is studied across long periods of time to look for trends or cycles of variability, such as the changes in wind patterns, ocean surface temperatures, and precipitation. Snow in skiing locations isn’t proof that climate change is not happening.

“The warming is due to natural variation…”

This is a very common argument, the denier does not argue against the existence of climate change, generously admitting the climate has *always* changed, but they do not believe that humans are responsible for it.

The IPCC has concluded that the warming of the last century, especially from the 1970s, falls outside the bounds of natural variability.

Let’s walk down memory lane and look at what the IPCC has been saying to us for 26 years. And keep in mind that the IPCC reports are the most comprehensive, global, and peer-reviewed studies on climate change ever written by anyone, bringing together the work of over 800 scientists, more than 450 lead authors from more than 130 countries, and more than 2,500 expert reviewers. In short, the IPCC reports are humanity’s best attempt to date at getting the science right.

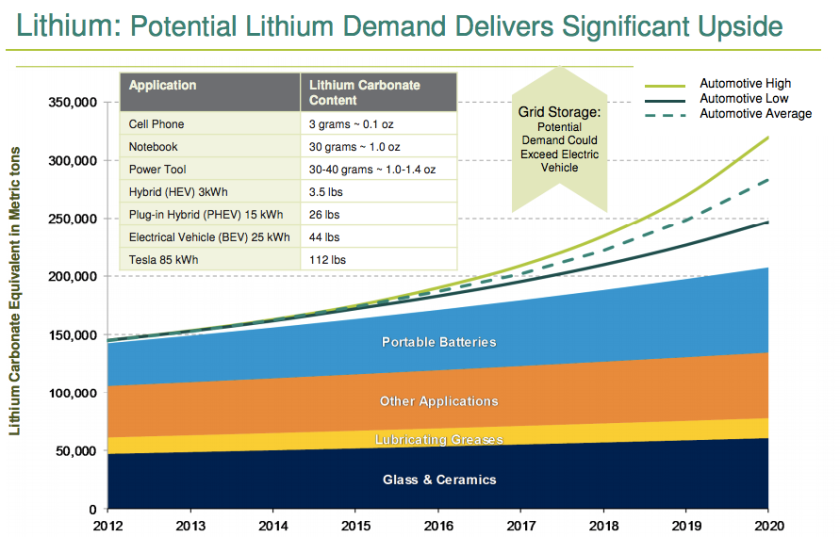

Over the last 800,000 years, Earth’s climate has been cooler than today on average, with a natural cycle between ice ages and warmer interglacial periods. Over the last 10,000 years (since the end of the last ice age) we have lived in a relatively warm period with stable CO2 concentration. Humanity has flourished during this period. Some regional changes have occurred – long-term droughts have taken place in Africa and North America, and the Asian monsoon has changed frequency and intensity – but these have not been part of a consistent global pattern.

The rate of CO2 accumulation due to our emissions in the last 200 years looks very unusual in this context (see chart above). Atmospheric concentrations are now well outside the 800,000-year natural cycle and temperatures would be expected to rise as a result.

Moreover, the IPCC in 1995, in its second assessment report included a sentence that hit the headlines worldwide:

“The balance of evidence suggests a discernible human influence on global climate”

By 2001, IPPC’s third report was even clearer:

“There is an new and stronger evidence that most of the warming observed over the last 50 years is attributable to human activities.”

By 2007, in it’s fourth report, IPCC spoke more strongly still:

“Human induced warming of the climate system is widespread”

In 2013, in the 5th Assessment Report, they stated,

“It is extremely likely that human influence on climate caused more than half of the observed increase in global average surface temperature from 1951 to 2010”

Human activity has led to atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide that are unprecedented in at least the last 800,000 years.

There is, therefore, a clear distinction to be made between what is “natural variability” and what is our contribution.

“The amount of warming is insignificant…”

The European Geosciences Union published a study in April 2016 that examined the impact of a 1.5°C vs. a 2.0°C (bear in mind we are at 0.8°C now, without the slightest chance of slowing down) temperature increase by the end of the century. It found that the jump from 1.5 – 2°C, a third more of an increase, raises the impact by about that same fraction, on most of the natural phenomena the study covered. Heat waves would last around a third longer, rain storms would be about a third more intense, the increase in sea level would be that much higher and the percentage of tropical coral reefs at risk of severe degradation would be roughly that much greater.

But in other cases, that extra increase in temperature makes things ever more dire. At 1.5°C, the study found that tropical coral reefs stand a chance of adapting and reversing a portion of their die-off in the last half of the century. But at 2°C, the chance of recovery disappears. Tropical corals are virtually wiped out by the turn of the century.

With a 1.5°C rise in temperature, the Mediterranean area is forecast to have about 9% less fresh water available. At 2°C, that water deficit nearly doubles. So does the decrease in wheat and maize harvest in the tropics.

Bottom line: It may look small but it’s a huge deal.

“The benefits will outweigh the problems”

When people talk of alleged benefits of climate change, they are usually talking about agriculture. The argument says that the increased concentrations of CO2 will give a boost to crop harvests leading to larger yields.

This is laughable

Climate change will slow the global yield growth because high temperatures result in shorter growing seasons. Shifting rainfall patterns can also reduce crop yields. Climate trends are already believed to be diminishing global yields of maize and wheat. These symptoms will only worsen as temperatures and extreme weather events become more common. If climate change is allowed to reach a point where the biophysical threshold is exceeded, as would be the case on current emission trajectories, then crop failure will become normal. Also, the severest risks are faced by countries with high existing poverty and dependence on agriculture for livelihoods. Even at “low” levels of warming, vulnerable areas will suffer serious impacts.

- Sub-Saharan Africa, according to the World Economic Forum, at 1.5°C warming by 2030 would bring about a 40% loss in maize cropping areas;

- South East Asia, in a 2°C would experience unprecedented heat extremes in 60%-70% of their areas.

Agricultural productivity is at risk, not only in developing countries but also in breadbasket regions such as North and South America, the Black Sea and Australia.

Moreover, in October 2015, a study published in Nature estimated that the world could see a 23% drop in global economic output by 2100 due to a changing climate, compared to a world in which climate change is not taking place. The coauthor of the study had this to say,

“Historically, people have considered a 20% decline in global GDP to be a black swan: a low-probability catastrophe – Instead, we’re finding it’s more like the middle-of-the-road forecast.”

“Technology will come to the rescue…”

Deniers who make this case seemingly acknowledge climate change, yet they are optimistic believers in technology being the be-all end-all and that geo-engineering will save us from the clutches of global warming. There are two things I find problematic about this approach:

- I think this argument is akin to the “We almost discovered nuclear fusion- we’re only 20 years away!” argument, which stipulates that the nuclear fusion is at any given point in time 20 years away. It takes into account that we have not developed the appropriate technologies to “save” us from climate change, and when we do, there is still a maddening lag between the innovation and deployment. Not to mention the fact we still have not identified which technologies can do the greatest good in the shortest time so we cannot fly blindly in a vague hope that tech will rescue us;

- Such an approach fights the “symptoms” of climate change, not the cause of it, meaning that it entrenches our extremely wasteful and inefficient ways that have brought on climate change in the first place.

None of this is to say that I do not believe that technology will play a pivotal role in our transition, of course, it will! But we cannot afford to rely entirely on waiting for carbon capture and storage and the likes to become a deployable and scalable economic reality.

“We shouldn’t wreck the economy to fix the problem when it’s still uncertain!”

When you really get down do it, people will just tell you what their ultimate bottom-line is. If we don’t know with absolute confidence how much you warmer and what the local and regional impact will be perhaps we’d better not committing ourselves to costly reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.

I have written a post on the employment benefits tied to jobs in the renewable energy sector, and there are a plethora of studies pointing to the huge costs of climate change inaction, amongst these, a new study by scholars from the LSE, published last year in Nature Climate Change, offers a daunting scenario.

Climate change can affect the economy in myriad ways; including the extent to which people can perform their jobs, how productive they are at work, and the effects of shifting temperatures and precipitation patterns on things like agricultural yields or manufacturing processes. These factors help determine our “economic output” — all the goods and services produced by an economy.

In spite of the fact that there is disagreement on how much exactly economies will be affected, we know the cost of inaction will be immense. With the information at our disposal, it would be foolish and dangerous to assume that reducing emissions will cost more than coping with a changing climate.

Good luck with your “debate” and let me know how it goes.