One of President Trump’s most resounding battle cries during the election was the bold promise to invest in infrastructure. I am going to argue that Mr. Trump should focus on upgrading the US electric grid, most of which is +25 years old and some parts are even +40 years old.

100 years ago, when the original electric grid was built, it was not conceivable to imagine consumers choosing their distributed generation because an energy generator would burn a fossil fuel and create electricity, which would be transmitted to consumer’s homes and that was that.

But the advent of renewable energy and small, private wind and solar producers means that today’s grid is nearing the end of its useful life both physically and functionally. Today the world is much more mobile, fluid, and flexible, but the grid has not kept up. A smart grid is set to provide real benefits to all stakeholders, including consumers, utilities, and regulators.

For starters, it will bring environmental benefits: through efficient use of energy and existing capacity by using digital communications technology to detect and react to local changes in usage and it will give customers options and choices to change their behavior when it comes to the price and type of power they use, and when to use that energy resource efficiently.

Efficiency is optimized thanks to a smart grid because of a two-way power flow and the integration of energy storage capacity, which would allow consumers to take energy when they need it, and the feed it back (in the case of solar/ wind producers) into the grid when prices are higher or store it. However, today, the grid is not really equipped to handle neither reverse power flows nor storage.

The Grid: An Economy Enhancing Investment

Although Americans bemoan the disrepair of their dilapidated roads, transit, and airports in countless NYT editorial pieces, the Trump Administration must consider the unseen but increasingly crucial issue of reinventing the power grid.

While the electric utility sector may not be the most riveting, the U.S. smart grid expenditures forecasts at more than $3 billion in 2017 (PDF) and the global smart grid market expected to surpass $400 billion worldwide by 2020. Navigant Research, a clean tech consultancy, reports on worldwide revenues for smart grid IT (information technology) software and services, are expected to grow from $12.8 billion in 2017 to more than $21.4 billion in 2026.

The private sector is stepping up. Not only tech companies such as Oracle, IBM, SAS, Teradata, EMC, and SAP but also utility giants such as General Electric, Siemens, ABB, Schneider Electric, and Toshiba are getting involved in smart grid IT.

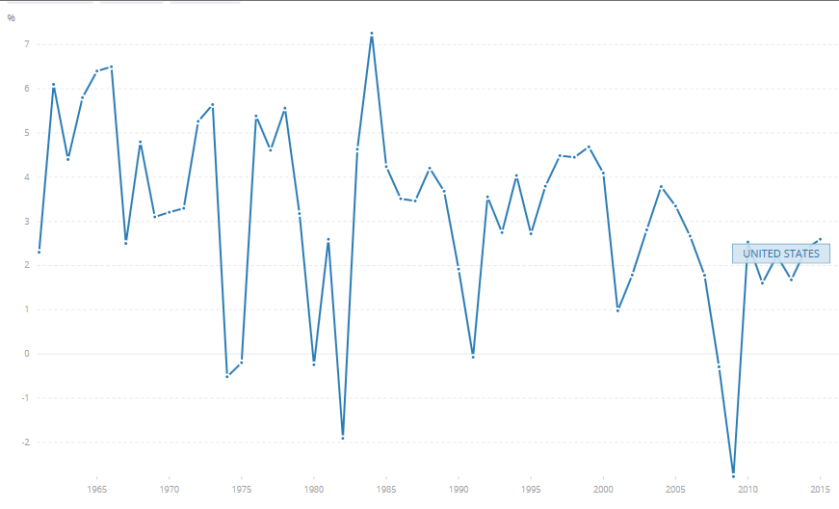

Moreover, with historically low-interest rates (for now) and the potential for infrastructure projects to deliver long-run economic returns, many believe infrastructure investment could kick-start the country’s slowish GDP growth. Yet in spite of a body of economic evidence which points to clear benefits derived from infrastructure investment, simply building more roads will not guarantee economic growth on its own, as the textbook examples: Japan and China indicate. This lesson is particularly important considering the falling returns from public investment in U.S. highways.

U.S GDP Growth % 1965-2015

And this brings us to the grid: aiming investment at the grid would improve conditions for millions of people as well as address the needs of the private sector.

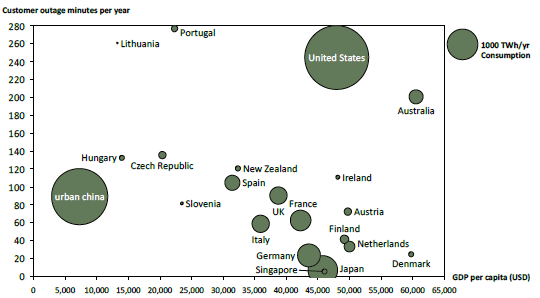

The average American endures 6+ hours of blackouts a year, which amounts to at least $150 billion for the public and private sector each year — about $500 for every man, woman, and child, – that is remarkably bad for a developed country. Power outages in the USA are mostly caused by the effect harsh weather on the aging grid. Heavy industry tends to be most affected by tiny outages, and this example from Saviva Research is painfully illustrative:

A robotic manufacturing facility owned by Toshiba experienced a 0.4-second outage, causing each robot to become asynchronous with the grid; thus short circuiting chips and circuits. Toshiba spent the next 3 months reprogramming each robot, leading to an estimated economic loss of $500m.

International Grid Reliability

In the U.S, investments in the power grid lag behind Europe. Across the pond, since 2000, the U.K., Italy, Spain, France and Germany have spent a combined $150.3 billion on energy-efficiency programs, compared with $96.7 billion for the U.S, according to data by Bloomberg New Energy Finance. Moreover, according to a 2015 report by energy consultancy, the Rocky Mountain Institute the, the U.S. needs about $2 trillion in grid upgrades by 2030.

The Smart Grid: A Strategic Economy-Enhancing Objective

Yet there is much that the government and the private sector should seek to unpack about consumer behavior, strategic implications, governance, and decision-making regarding the grid, before committing to such a massive investment. The incoming investments in the next decades offer a historically important opportunity to rethink how the whole system of power generation, transmission, and usage operates.

Here’s just one consideration: ownership. Future smart grids are likely to have multiple ownerships, which will most likely span across:

- The government: through publicly owned power and transmission lines;

- The private sector: independent wind farms developers and operators or utility-owned generators;

- Private citizens: owners of household-level battery backup systems or rooftop solar panels.

All it really means is that combining forces for a specific project makes it possible to focus each parties’ inherent assets in the way that best reduces their shared risks, and reduced risk means a lower cost of borrowing, and therefore: cheaper projects.

As J. Michael Barrett explains: If the federal or state government can reduce the investment risk of the project by providing seed capital, issuing tax-exempt bonds, and/or signing a power purchase agreement to buy energy for a guaranteed period of time, the private sector can then provide investment capital at more favorable rates because total project risk is reduced. When all the parties share the up-front construction costs (and risk), promote open access to usable land, and lock-in the commitment of long-term users.

Finally, the most plausible way forward is to invest in new technologies opposed to retrofitting them later, an educated, unideological clear-eyed strategic effort to make the most of these investments would ensure both improved operations improvements in resilience and adaptability across the board.

tl;dr: A functioning integrated electricity system is a basic public good, imperative to the wealth, safety, and wellbeing of any modern society. In the context of a rapidly evolving energy infrastructure landscape, taking a strategic stance during the development of the smart grid in the USA will determine how much value is captured and who will capture it.

Read more: here The Energy Infrastructure that the US Really Needs